The Northern Avian Physiology (NAP) lab at Northern Michigan University explores the physiological mechanisms supporting astounding feats in birds–ranging from long-distance migratory flight to survival in frigid winter temperatures–to better understand resilience to environmental changes.

Flexibility in response to different cues

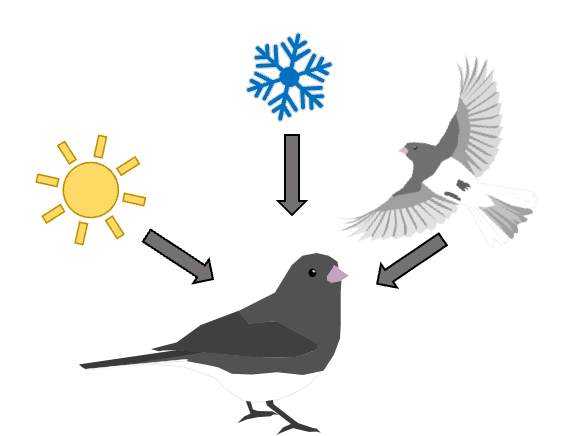

Temperate winters are exceptionally challenging for animals: resources are scarce and cold temperatures require that resident warm-blooded animals expend energy for heat production to maintain their body temperature. To meet this demand, birds that stick it out through the winter enlarge their muscles, burn more fat, and boost their ability to generate heat by shivering. Migratory birds, however, seasonally exploit these same habitats to breed but escape the harshest winter conditions through a series of long-duration migratory flights. In response to day length changes, these migratory birds improve their ability to deliver fat as a fuel to their enlarged flight muscles. Because dealing with the cold and preparing for migratory flight show similar physiological changes (e.g. enlarged muscles and a reliance on fat as fuel), this is a great system to study whether these related birds retain the ability to fully respond to both temperature and day length cues.

Calcium dynamics in the muscle

Up to half of an animal’s resting energy use can be attributed to the cost of calcium regulation in muscle. Calcium can signal for wide-ranging physiological changes with broad implications for organismal health, such as fuel use, exercise capacity, obesity, and heat generation, so it’s vital that it be carefully regulated. One important component of calcium regulation is sarcolipin (SLN), a small regulatory protein that uncouples calcium transport from the energy-burning activity of the SERCA enzyme and generates excess heat as a byproduct. While mice will increase SLN in the muscle to generate heat in the cold, we have actually found the opposite pattern in birds in the cold, while migratory birds—which should theoretically have the most efficient muscle during their long-distance flights—actually have higher SLN expression. These puzzling patterns raise many questions about the function of SLN in birds and the role of calcium signaling in coordinating many of the physiological changes in responses to the environment in the previous section.

Flexible responses in a changing world

Because an animal’s genetic toolkit is limited, the potential to entrain physiological changes to different environmental stimuli may enable a broader range of responses to environmental variation and therefore greater resilience in a changing world.